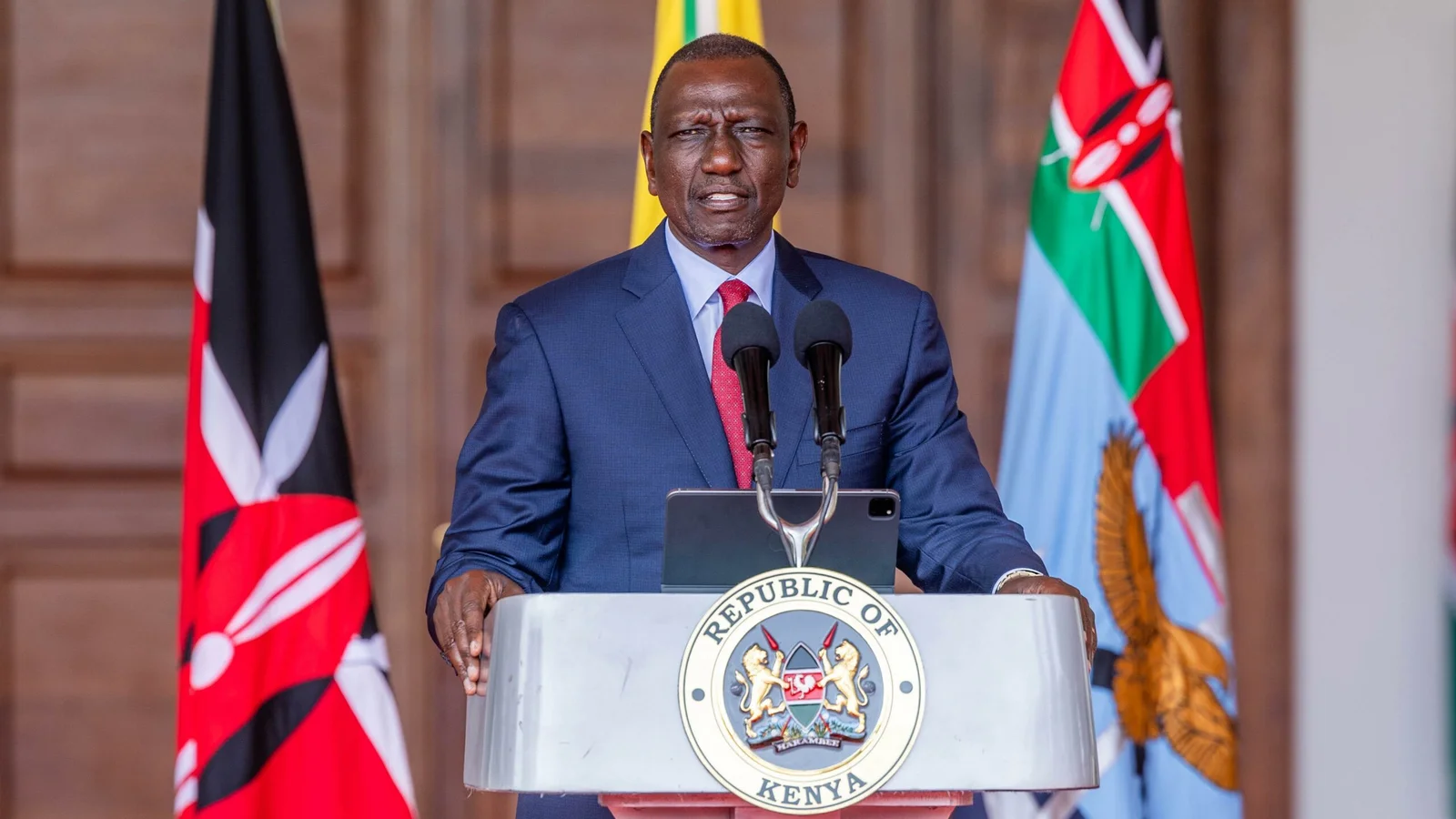

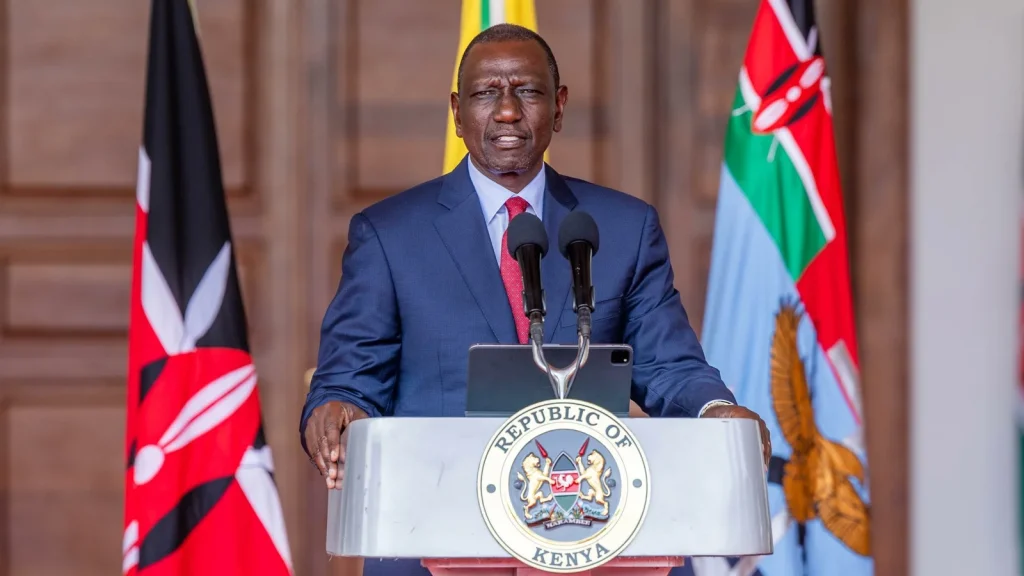

President William Ruto. PHOTO/UGC.

By ABDULHALIM SHERMAN

President William Ruto has ignited a political storm with a single, devastating claim that a parliamentary committee had allegedly been bribed to smooth the passage of anti–money laundering legislation.

He named a figure a Sh10 million and invoked “raw intelligence,” a tantalising whiff of secret knowledge only accessible to the highest echelons of power. In that moment, a fire was lit beneath Kenya’s shaky democratic structure, and the world watched as the embers spread.

Emerging reports now suggest that the origin of that bribe was neither elusive nor mysterious. Betting companies; industries flush with cash and unassuaged by tightening financial regulations, reportedly channelled funds to that parliamentary committee to influence the law before its approval.

What is remarkable is that these companies are not faceless commercial players; instead, they seem to be part of a cartel intricately tied to powerful brokers, wheeler-dealers who act as proxies for those perched at the apex of the Kenya Kwanza government.

This is not merely business. It is a calculated infiltration of democratic institutions by financial interests cloaked in the camouflage of governmental affiliation. Who truly benefited from the changes made to the anti–money laundering laws, if not those close to power?

Since taking office following the highly contested 2022 elections, the Kenya Kwanza administration has seen MPs; both in the National Assembly and the Senate, eager to deliver on government-sponsored legislation.

Bills like Affordable Housing, NSSF reforms, and the Social Health Authority Act have sailed through, often at odds with the will of the electorate. The Ruto administration’s legislative engine seems powered less by democratic mandate and more by political expediency.

This controversy comes on the heels of the historic Gen Z–led protests that shook Kenya in June and July 2024. Triggered by the 2024/25 Finance Bill; passed in defiance of overwhelming public opposition, the protests transformed from an economic uprising into a democratic reckoning.

For the first time in Kenya’s post-colonial history, young citizens organised leaderless demonstrations that paralysed major cities, overwhelmed security forces, forced their way into Parliament and ultimately forced President Ruto to withdraw key sections of the Finance Bill.

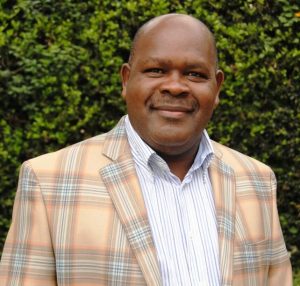

Tharaka MP Gitonga Murugara chairs the National Assembly’s Justice and Legal Affairs Committee (JLAC). PHOTO/UGC.

Now, with threats of censure and impeachment looming from both houses of Parliament, Kenyans watch, riveted. Is this the death knell of accountability, or merely another turn in an unending power struggle?

The spotlight since Ruto’s statement has fallen squarely on the National Assembly’s Justice and Legal Affairs Committee, commonly known as JLAC; a 15‑member body that shepherded amendments to anti–money laundering and terrorism financing laws. Chaired by Tharaka MP Gitonga Murugara, the committee was accused of accepting undue inducement.

Murugara’s response was unequivocal: “The committee did not solicit and did not receive any inducement of any kind whatsoever … as alleged or at all.” He reiterated that the Bill was government-sponsored, introduced by the Majority Leader Kimani Ichung’wah, and challenged the President to name names.

This was not a polite diplomatic denial. It was a defiant call: “Produce evidence, or retract your claim.”

A day prior, speaking at a joint parliamentary group gathering of the ruling United Democratic Alliance and the Orange Democratic Movement, President Ruto sharpened his accusations, again naming JLAC as a locus of corruption: “Do you, for example, know that a few members of your committee collected Sh10 million so that you don’t pass that law on anti–money laundering?” he asked, visibly placing his confidence in the “raw intelligence” accessible to his office.

By casting suspicion around the committee; comprising high-profile names such as Deputy Speaker Gladys Boss, Mwengi Mutuse, TJ Kajwang’, Otiende Amollo, and others, Ruto not only defamed reputations but intentionally struck at the institutions that underpin democratic scrutiny.

To understand the stakes, one must revisit the legislative trajectory of the anti–money laundering bill. Initially passed by the National Assembly in April, the Bill proposed amendments to ten existing Acts; including the Proceeds of Crime and Anti–Money Laundering Act, the Prevention of Terrorism Act, and the Betting, Lotteries and Gaming Act, among others.

The proposed changes aimed to address gaps identified by regional and international watchdogs (like the Eastern and Southern Africa Anti–Money Laundering Group and the Financial Action Task Force), which had grey‑listed Kenya over its financial vulnerabilities.

As domestic institutions fracture, Kenya’s international reputation is also under siege. The United States Congress has reportedly formed a bi-partisan committee to review Kenya’s status as a Major Non-NATO Ally (MNNA); a designation that grants Nairobi military and economic privileges reserved for Washington’s closest partners.

At the heart of this review are growing concerns that Kenya is playing a destabilising role in East Africa. Intelligence leaks suggest the Ruto government may be tacitly supporting rebel factions in Sudan and the Democratic Republic of Congo. More alarmingly, claims have emerged that Ruto; or officials in his orbit, held discreet meetings with members of the terrorist group Al-Shabaab.

President Ruto called out MPs for demanding money from members of the Executive who appear before Parliament for accountability during the 9th Devolution Conference held in Homa Bay County. PHOTO/Presidency.

Additionally, Kenya is increasingly described in global intelligence circles as a burgeoning hub for money laundering, arms smuggling, and drug trafficking. Nairobi’s lax financial regulations and shell corporations have, according to watchdogs, made it a fertile ground for transnational crime syndicates.

Yet, Ruto objected to a specific clause: it sought to restructure the tenure of the outgoing Director‑General of the Financial Reporting Centre, Saitoti Maika. The Bill proposed transitioning his existing term into a single, non-renewable six-year mandate; an amendment that could cumulatively extend his service beyond ten years.

The President viewed this as a breach of the constitutional architecture governing independent offices (Chapter 15), whose maximum term is capped at eight years. He urged that any current office holder should complete their tenure under the terms applicable at the time of appointment, a position grounded in constitutional continuity, if not controversy.

While Ruto did not accuse Maika of wrongdoing, and nor is there any public allegation against him, the tug-of-war over institutional integrity and executive overreach was laid bare.

By June, Ruto signed into law the amended anti‑money laundering legislation, with his office framing it as a major advancement in sealing long-standing loopholes. “The amended law seals long-standing loopholes that have enabled the misuse of property transactions and shell companies for illegal financial activities,” State House declared.

But the questions remain. Who truly shaped these changes? Was the State House’s claim about closing loopholes earnest, or a cover for a law tailored to serve private and proximate interests?

What does all this mean, not just in legal or political terms, but at the emotional core of Kenyans’ relationship with their democracy? At its foundation lies trust: the belief that elected officials legislate for public good. When that foundation is rocked by allegations of bribery, the fissures run deep. The sense of betrayal is not abstract, it is visceral.

Kenyans see institutions meant to safeguard democracy being manoeuvred for clandestine agendas. They observe a President brandishing “intelligence” without substantiation, MPs gazing across aisles not for consensus, but for protection. And amid it all, ordinary citizens wonder: is democracy in Kenya a living entity or a marionette with wires pulled from hidden rooms?

The narrative now is one of duel: the executive versus the legislature. Parliament’s threatened censure may force the President’s hand or deepen the rupture. If accountability prevails, we may see names named, evidence released, and trust tentatively restored. If not, the real damage could be to Kenya’s democratic architecture itself.

History will judge whether this was a cleansing fire; flames incinerating corruption into clarity, or an inferno that consumed the trust and legitimacy of governance.