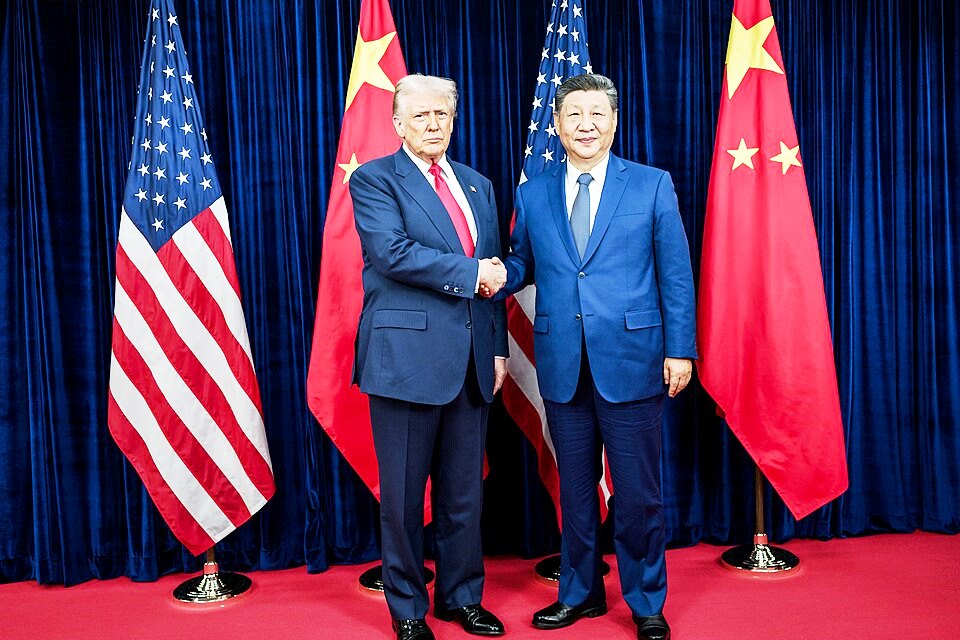

US President Donald Trump ordered the invasion of Venezuela by US troops. PHOTO/Whitehouse.

By TIM ALLEN

The political and economic turmoil surrounding the ouster of Venezuela President Nicolás Maduro has become a focal point for global geopolitics, particularly with respect to the country’s vast oil reserves.

Long regarded as possessing some of the world’s largest proven oil reserves; estimated at 303 billion barrels, predominantly concentrated in the Orinoco Belt, Venezuela has the potential to play a pivotal role in the future of global energy.

However, the country’s current political and economic crises, compounded by U.S. sanctions, have created a complex battle over control of its oil resources, with China emerging as a critical player.

The United States has a long history of military and economic interventions in resource-rich nations, often framed as efforts to restore political stability, promote democracy, or counter regional adversaries. However, the underlying financial and strategic interests, particularly in securing access to vital energy resources; are significant drivers.

Take Iraq, for instance. In the early 2000s, the administration of George W. Bush led the charge to invade Iraq, ostensibly to eliminate weapons of mass destruction (WMDs). However, one of the lasting narratives in the aftermath of the 2003 invasion is the role that Iraq’s oil reserves and its decision to trade oil in euros (rather than U.S. dollars) played in drawing the ire of the West.

This shift threatened the global dominance of the dollar in oil trading, a move that many analysts believe was a catalyst for the U.S. intervention. By the time the U.S. had toppled Saddam Hussein, Iraq’s oil was once again traded in U.S. dollars, reinforcing the dominance of the greenback in global markets.

Similarly, U.S. intervention in Libya in 2011, during the NATO-backed uprising against Muammar Gaddafi, is often viewed through the lens of securing control over North African oil. Gaddafi’s plans to create a pan-African currency system based on gold were seen as a potential threat to the U.S. dollar’s position as the global reserve currency. These examples highlight the financial dimensions of international conflicts, where control of oil and monetary systems often underpins military intervention.

In the case of Venezuela, these historical precedents seem eerily familiar. As, Robert Kiyosaki, American financial expert and author, points out, modern conflicts often evolve from financial isolation, including sanctions, rather than conventional military engagement.

The U.S. strategy toward Venezuela has been a potent combination of sanctions, diplomatic pressure, and military threats aimed at destablising the regime of President Nicolás Maduro. These actions have isolated Venezuela from global financial systems, triggering hyperinflation, economic collapse, and a mass exodus of its population. Yet, the key underlying issue remains Venezuela’s vast energy resources and the battle to control them.

The crux of the matter, according to Kiyosaki, is that the financial sanctions imposed on Venezuela target more than just its political system; they aim to strangle the country’s ability to leverage its natural resources, oil in particular, on the global market.

The U.S. and its allies have deployed a range of financial tools: sanctions on Venezuela’s state-owned oil company, PDVSA; restrictions on shipping companies and ports; and blocking access to international payment systems.

However, this is where China has stepped in. While the U.S. has imposed punitive measures, China has provided Venezuela with crucial economic and financial support. Venezuela’s oil exports to China have surged in recent years, with China becoming the country’s largest buyer, accounting for more than half of its oil exports in 2024. Moreover, Beijing has used Venezuela’s oil as a form of debt repayment, with oil-for-debt structures offering Venezuela a lifeline as it struggles to cope with sanctions.

China’s role is part of a broader strategy to establish long-term, non-dollar trade routes for oil, thereby reducing its reliance on U.S. financial systems. Instead of military force, China has used economic leverage to secure its energy interests. Through long-term purchase agreements and shadow shipping networks, China has managed to secure stable supplies of Venezuelan crude while avoiding U.S. sanctions.

This system of financial warfare—using sanctions, trade agreements, and debt restructuring to achieve geopolitical ends, is what Kiyosaki refers to when he talks about a new type of conflict: one that is waged not in battlefields, but in the economic and financial arenas.

As Kiyosaki argues, Venezuela’s oil is more than just a commodity, it is a vital cog in the global financial system. Control over Venezuela’s oil means control over global cash flow and, crucially, currency dominance. The U.S. dollar has long been the world’s primary reserve currency, and oil sales are typically settled in dollars.

This is not an accident, but rather the result of decades of U.S. financial policy and influence. If countries like Venezuela, Iraq, and Iran choose to bypass the dollar in their oil transactions, they not only threaten the U.S.’s financial supremacy but also create opportunities for alternatives like China’s yuan.

This is where the current struggle over Venezuela becomes a high-stakes game for the future of the global energy system. The U.S. is intent on reversing the growing influence of China in Latin America, particularly in terms of energy. A successful ouster of Maduro, potentially followed by the lifting of sanctions, could see Venezuela’s oil flow redirected back to U.S. refineries.

The U.S. Gulf Coast, with its capacity to process heavy crude, would become the natural destination for Venezuelan oil, and U.S. refiners could benefit from increased access to low-cost, high-quality oil from Venezuela’s Orinoco Belt. The return of American oil majors, such as Chevron, to Venezuela would further cement the U.S.’s dominant role in the country’s oil industry.

In the aftermath of a potential regime change, the road to revitalising Venezuela’s oil sector is long and fraught with challenges. Venezuela’s oil production has plummeted in recent years, from a peak of 3.7 million barrels per day (bpd) in the 1970s to a meagre 900,000 bpd in 2024.

Despite the country’s vast reserves, underinvestment, mismanagement, and sanctions have crippled its ability to increase output. Even if political stability were restored, it could take years for Venezuela’s oil industry to return to full capacity.

For Western oil companies, the allure of Venezuela’s oil is undeniable. However, the legal and financial risks associated with operating in the country, coupled with Venezuela’s outstanding debts to international oil firms, complicate the prospects for large-scale investment. Nevertheless, the opportunity to access some of the world’s cheapest oil is a tantalising prospect for companies like Chevron, ExxonMobil, and Shell, all of which have long histories in Venezuela.

As Kiyosaki aptly points out, the battle over Venezuela’s oil is not simply about the oil itself but about who controls the financial system that underpins the global trade in energy. The U.S. and China are engaged in a silent, yet powerful struggle to control not just Venezuela’s vast energy resources but the future of the global economic order.

The U.S., with its military and financial might, seeks to break the chains of Chinese influence, while Beijing employs economic warfare to secure access to vital energy supplies. In this new era of financial warfare, control over oil is as much about the system of trade, currency, and debt as it is about the resource itself.