US law makers on Wednesday approved a bill requiring the Beijing-based company ByteDance to sell its subsidiary Tik Tok or face a nationwide ban. PHOTO/Wikipedia.

By MORRIS ODHIAMBO

If you are involved in the field of strategic studies, you probably know something about the three traditional “dimensions” of war: land, air and maritime (sea). These three held sway in strategic studies for many years. However, recent technological advances, the post-Cold War technological explosion, and the advent of Electronic Warfare, conspired to create the fourth dimension of war, that is, cyberspace.

What this actually means, particularly from international relations and Pan Africanist perspectives, is the subject of my reflections today.

Two related historical facts have led to the advent of cyberspace war: the invention and widespread use of internet technology (from its roots largely in the US military), and the global connectivity, use and innovation that has come with it. States continue to use different platforms to execute this war. These include policies, laws and regulations, active surveillance and intelligence gathering, etc.

I have been monitoring the evolving war over Tik Tok between the US and China. This war has come to epitomise the beginning, continuation, or escalation, of the cyberspace war between these two economic giants.

About two weeks ago, the US Congress passed a law called “Protecting Americans from Foreign Adversaries Controlled Applications Act”. The law makes it an offence to maintain (or enable the maintenance of), distribute (or enable the distribution of) or update (or enable the updating of), social media applications designated as being controlled by US foreign adversaries, unless “such applications are exempted under a qualified divestiture as determined by the US president.”

This law, therefore, gives the US president wide discretionary powers to determine what is or is not a security threat to the US in terms of technological applications. And it will not only apply to Tik Tok, which was the primary motivation for its passing, it will also apply to any other foreign controlled application that the president deems to be against the demands of national security.

However, the most important thing in this emerging situation is not the new law and what the Foreign Policy establishment in Washington DC thinks of its trajectory. In my view, the most important thing, which plays to the advantage of ByteDance, the owner of the technology, is the fact that many, if not most, American citizens and citizen pressure groups, are largely opposed to the law.

During its debate and passage, many congressmen and women revealed how their constituents had inundated them with calls to oppose the law. Indeed, a few of them opposed it on that basis.

The Center for Democracy & Technology (CDT) is among the citizen pressure groups that opposed the law. It did so on the basis that it infringes on the “First Amendment rights of Americans across the country who rely on Tik Tok for information, communication, advocacy, and entertainment.” A similar position was taken by the American Civil Liberties Union, Electronic Frontier Foundation (EFF), and Fight for the Future.

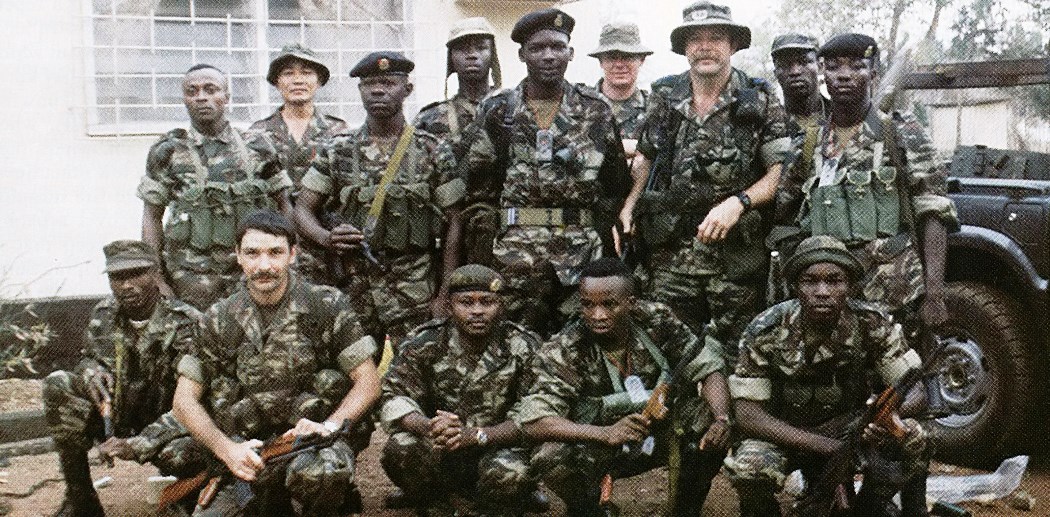

![]()

Icons of some of the leading social media platforms that are at the centre of the cyberspace technological warfare. PHOTO/UGC.

Supporters of the law largely regurgitated what the government was saying about security. One blogger noted the following: “The social media application Tik Tok is a unique threat posed to U.S. national security through its ownership by ByteDance – a Chinese company answerable by law to the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) and Chinese intelligence services.”

The blogger went on to say, “This relationship allows ByteDance to gather extensive data on U.S. citizens, potentially exposing their personal information to the Chinese government. Moreover, this vulnerability leaves the door open for China to manipulate the platform to influence and mislead Americans. The proven national security risks associated with Tik Tok cannot be adequately addressed as long as ByteDance remains its owner.”

Part of the conversation is, of course, the fact that China continues to ban most of the West’s popular social media sites from operating in the country.

But what does all this mean to the African continent? How have African countries fared in the field of technological invention? Is Africa part of the emerging technological war? What, if anything, is the significance of technology to Pan Africanist conversations?

On the continent, technology is looked at from a fairly narrow perspective; basically as an enabler of development (in the sense of socioeconomic progress). Africa is a net consumer of technology. The myth of technological transfer remains just that; a myth. Even though the African Union has an elaborate institutional layout to deal with matters of technology, I suspect there isn’t much to write home about its achievements. Nonetheless, technology continues to be a key cog in many countries foreign policy discourses, diplomacy and so-called development partnerships.

There is evidence that countries are actively adopting and using technology to solve social problems, apart from the inevitable surveillance and intelligence gathering. My research shows, for example, that the following countries have adopted satellite technology for different uses: Egypt, South Africa, Kenya, Nigeria, Algeria, Morocco, Ethiopia, Angola, Ghana, Mauritius, Sudan, Tunisia, Uganda and Zimbabwe. The use of drones is not only restricted to security matters, but also social service provision.

From my observation, African leaders are not overly concerned with the technological warfare that is escalating between the US and China. This is largely a reflection of the continent’s weak agency in international affairs. The fact remains that states use technology to influence the behaviour of other states.

In my view, discussions about a possible ban on Tik Tok in Kenya, for example, are more an indication of external diplomatic pressure, than rational policy choices or reactions to domestic concerns.